A structured phonics programme puts a strong emphasis on reading and writing skills, ensuring that most pupils exceed the expectations.

Explore-

▸

Nursery & Pre-Prep

-

▸

Prep

Beyond the curriculum we encourage our pupils to take on responsibility and they thrive on Leadership opportunities.

Explore -

▸

Senior

At St Lawrence College we offer a supportive, caring and challenging environment, founded on traditional Christian values, where children are given every opportunity to fulfil their potential.

Welcome to Senior School -

▸

Sixth Form

St Lawrence College aims for educational excellence, and nearly all of the Upper Sixth will continue to Higher Education at University.

Welcome to Sixth Form

General The Lord Dannatt (former Chief of the General Staff – Head of the Army)

General Francis Richard Dannatt, Baron Dannatt, GCB, CBE, MC, DL (born 23 December 1950) is a retired senior British Army officer and member of the House of Lords. He was Chief of the General Staff (head of the Army) from 2006 to 2009.

Dannatt was commissioned into the Green Howards in 1971, and his first tour of duty was in Belfast as a platoon commander. During his second tour of duty, also in Northern Ireland, Dannatt was awarded the Military Cross. Following a major stroke in 1977, Dannatt considered leaving the Army, but was encouraged by his commanding officer (CO) to stay. After Staff College, he became a company commander and eventually took command of the Green Howards in 1989. He attended and then commanded the Higher Command and Staff Course, after which he was promoted to brigadier. Dannatt was given command of 4th Armoured Brigade in 1994 and commanded the British component of the Implementation Force (IFOR) the following year.

Dannatt took command of 3rd Mechanised Division in 1999 and simultaneously commanded British forces in Kosovo. After a brief tour in Bosnia, he was appointed Assistant Chief of the General Staff (ACGS). Following the attacks of 11 September 2001, he became involved in planning for subsequent operations in the Middle East. As Commander of the Allied Rapid Reaction Corps (ARRC), a role he assumed in 2003, Dannatt led the ARRC headquarters in planning for deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan. The ARRC served in Afghanistan in 2005, but by this time Dannatt was Commander-in-Chief, Land Command—the day-to-day commander of the British Army. He was responsible for implementing a controversial reorganisation of the infantry which eventually resulted in his regiment, the Green Howards, being amalgamated into the Yorkshire Regiment.

Dannatt was appointed Chief of the General Staff (CGS) in August 2006, succeeding General Sir Mike Jackson. Dannatt faced controversy over his outspokenness, in particular his calls for improved pay and conditions for soldiers and for a drawdown of operations in Iraq in order to better man those in Afghanistan. He also set about trying to increase his public profile, worried that he was not recognisable enough at a time when he had to defend the Army’s reputation against alleged prisoner abuse in Iraq. He later assisted with the formation of Help for Heroes to fund a swimming pool at Headley Court and, later in his tenure, brokered an agreement with the British press that allowed Prince Harry to serve in Afghanistan. He was succeeded as CGS by Sir David Richards and retired in 2009, taking up the largely honorary post of Constable of the Tower of London, which he held until July 2016.

Between November 2009 and the British general election in May 2010, Dannatt served as a defence adviser to Conservative Party leader David Cameron. Dannatt resigned when Cameron’s party formed a coalition government with the Liberal Democrats after the election produced a hung parliament, arguing that the Prime Minister should rely primarily on the advice of the incumbent service chiefs. Dannatt published an autobiography in 2010 and continues to be involved with a number of charities and organisations related to the armed forces. He is married with four children, one of whom served as an officer in the Grenadier Guards.

Baron Stevens of Kirkwhelpington (former Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police)

John Arthur Stevens, Baron Stevens of Kirkwhelpington, QPM, KStJ, DL, FRSA (born 21 October 1942) was Commissioner of Police of the Metropolis (head of the Metropolitan Police Service) from 2000 until 2005. From 1991 to 1996, he was Chief Constable of Northumbria Police before being appointed one of HM Inspectors of Constabulary in September 1996. He was then appointed Deputy Commissioner of the Met in 1998 until his promotion to Commissioner in 2000. He was a writer for the News of the World, for £7,000 an article, until his resignation as the hacking scandal progressed.

He sits in the House of Lords as a crossbencher.

Dee Koppang O’Leary (Film producer and director)

Dee Koppang O’Leary is a producer and director, known for The Crown (2016), Bridgerton (2020) and London 2012 Olympic Opening Ceremony: Isles of Wonder (2012). She has been married to Dermot O’Leary since September 14, 2012. They have one child.

Dee Koppang O’Leary is a 42-year-old producer and director.

She is best known for her directorial work on The Crown and Justin Bieber: All Around the World.

Her other screen credits include The Victoria’s Secret Fashion Show and reality show Ladies of London.

Humphrey Hawksley (BBC World Affairs Correspondent)

Humphrey Hawksley is an English journalist and author who has been a foreign correspondent for the BBC since the early 1980s. Hawksley was educated at St. Lawrence College, Ramsgate, [[Kent] after which he joined to Merchant Navy to work his passage to Australia.

Humphrey Hawksley has reported on key trends, events and conflicts from all over the world.

His work as a BBC foreign correspondent has taken him to crises on every continent. He was expelled from Sri Lanka, opened the BBC’s television bureau in China, arrested in Serbia and initiated a global campaign against enslaved children in the chocolate industry. The campaign continues today.

His television documentaries include The Curse of Gold and Bitter Sweet examining human rights abuse in global trade; Aid Under Scrutiny on the failures of international development; Old Man Atom that investigates the global nuclear industry; and Danger: Democracy at Work on the risks of bringing Western-style democracy too quickly to some societies.

Humphrey is the author of the acclaimed ‘Future History’ series Dragon Strike, Dragon Fire and The Third World War that explores world conflict. He has published four international thrillers, Ceremony of Innocence, Absolute Measures, Red Spirit and Security Breach, together with the non-fiction Democracy Kills: What’s so good about the Vote – a tie-in to his TV documentary on the pitfalls of the modern-day path to democracy from dictatorship.

His work has appeared in The Guardian, The Times, Financial Times, International Herald Tribune, Yale Global and other publications. His university lectures include Columbia, Cambridge, University College London and the London Business School. He is a regular speaker and panellist including at Intelligence Squared and the Royal Geographical Society, and he has presented his work and moderated at many literary festivals.

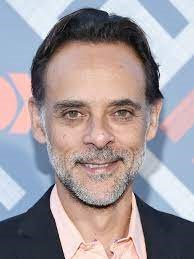

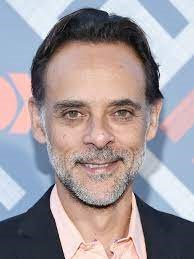

Alexander Siddiq (Actor)

Siddig El Tahir El Fadil El Siddig Abdurrahman Mohammed Ahmed Abdel Karim El Mahdi (born 21 November 1965) is a Sudanese-born English actor and director known professionally as Siddig El Fadil and subsequently as Alexander Siddig.

Siddig is best known for his roles as Dr. Julian Bashir in the television series Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, former terrorist Hamri Al-Assad in the sixth season of the series 24, and Doran Martell in the Game of Thrones series. He also starred in the films Syriana (2005), Kingdom of Heaven (2005), Hannibal (2006), A Lost Man (2007), Cairo Time (2009) and Inescapable (2012).

- Why St Lawrence?

St Lawrence College was recommended by a friend of my Mum. We were looking for a School that was inclusive. When I first came to England at four, I didn’t speak any English and could only read by the age of eight. I had therefore only been reading in English for four years by the time I got to St Lawrence. I had been given a place at Stowe because of my step-father’s connection as an Old Stoic but even though it was a magnificent place – absolutely stunning in fact – my mum was terrified that I would get beaten up a lot which was pretty common in schools in those days. This impression wasn’t helped by the Headmaster who said that there was another boy of colour there and that we would get on very well together. Immediately my mother said that they were going to find another school.

My mother was told that there is a school in Ramsgate that wasn’t crazily expensive that she should consider. She did and she liked it immediately. She liked Mr Crittenden as prospective House Master and Mr Harris as Headmaster. Harris was a very kindly fellow, not a firebrand, and a man of letters and my mum responded well to that. But St Lawrence was the ONLY school with a high proportion of children from all nationalities – the children of diplomats, farmers and missionaries etc and this changed everything for her.

Why were you boarding in the first place?

My mother had to work. We were living on our own for a year or so until she fell in love with, and married, another man. During this time she was working as a Press Officer for the Royal Court Theatre and had to work very unsocial hours and often very late. I was, in effect, a latch key kid. However I had a famous acting uncle, Malcolm McDowell, (my mother’s brother) who said that she had to get me out because it was difficult to raise a child like that and he was willing to pay the fees. It was a blessed relief for my mum that she could get me into school.

- My first impressions

St Lawrence College was a long way from home in London and the journey took three hours. I put on a brave face when I arrived but it was a bit overwhelming. As new boys we had a two or three week period of grace in which we had to learn all the rules and regulations. You got quizzed by the Head of House and House Monitors in a pretty hectic way – the School song, any question they wanted to ask you (for boarders). We had to get money for beer for the other boys who would come wandering into the dorm slightly drunk and often in the middle of the night. We learned very quickly and were pretty pre-occupied – there was no gentle settling in period. It was survival of the fittest!

I recall those days in February when we would be scraping the ice off the inside of the windows when we woke up. The condensation from our breath just froze but I was pretty adaptable though. I had come from Sudan and been to a difficult prep School so St Lawrence was a terrific place – and certainly the first multi–national school that I had attended.

I found friends fairly quickly at St Lawrence. Michael Wallace was one of these as was Sunil Mohinani. Vighnesh Padiachi and I became very good friends a bit later. He was an exceptional student and a great sportsman. Mark Dunnachie was a shining light in those days, always destined to be the Head Boy – incredibly nice, decent, fair and never getting into a fight with anyone! I was inclined to be a bit of a loner though. Michael and I got closer through the Christian Union which we took very seriously. This was a little odd on my part because I was a Muslim. I didn’t occur to me that I was a Muslim – my mother hadn’t told me. I think that Michael was in the choir as I had been in my previous school for the past four years at Prep School. Sunil was a very gentle soul and I was so diminutive and needed that then. I tried to keep my head down. There were a few monsters in Tower marauding through the school after 9 o’clock when the boys looked after the other boys. However people like Padi and Mark Dunnachie toughened up pretty quickly as a result. Mark was quite sensitive when he arrived but by the end he was Head of School. The multi-nationalism though was the key. Boys at Eton, Harrow and Stowe – the premium branded schools – were purely white and so wealthy there was no way that anything was going to touch them. They had servants and people to look after them. The boys coming to St Lawrence were of a different echelon financially and, although relatively well heeled, led comparatively normal lives. About 30% of us came from ethnic backgrounds and that just didn’t exist anywhere in the country at that time. Unsurprisingly all these factors ensured that we got on well with people from all backgrounds, colours, shapes and sizes. Colour certainly wasn’t an issue for us, quite the opposite. The culture and education at St Lawrence made us very accepting of others and very grounded.

- Were you a sportsman at school?

I enjoyed playing a number of sports. I was Captain of First XI School team and Captain of Lodge House Cricket in 1984. I took a lot of pride in my cricket and practised my slip fielding assiduously on Newlands. Cricket was a full time obsession in fact. I was too light weight to play rugby seriously but played in the Second XI as a fly half or full back. I played hockey too but it was SO cold up there on Newlands. We weren’t allowed to wear anything but shorts and a white shirt. I just used to dread it. Getting your hands hit by another hockey stick in the bitter cold was terrible!

- Who were your favourite teachers?

Mr Campbell was a Science teacher (Biology?) who was hilarious. He was a maverick and we liked him very much. Crittenden was a very gentle House Master and I liked him too. He could be tough when he needed to be particularly when dealing with the inevitable crisis when it arose eg when a teacher died of a heart attack on the squash courts or after a terrible accident. We called him ‘Cripple’ but I was lucky to have him as a House Master. He was such a sympathetic character when we were surrounded by the brutality of the boys.

However Binfield was my favourite teacher. He was both inspirational and a disciplinarian. As a lazy boy, Binfield got me a B at A Level English and with a B in Geography, my teachers certainly got something right! Binfield so loved what he was doing that he unlocked doors if you were prepared to listen – he was a Shakespeare fanatic. Binfield taught what every line meant and so even the most boring play can come alive for 12, 13 or 14 year olds. They just sat there loving it. Directing has always been a passion with its unravelling of the text, explaining it to your actors and getting them all to sing from the same hymn sheet – this is something that Binfield taught me. Mind you if we upset him, he would let you know but this was what made us read the poem or the play he requested. I was such a lazy pupil that had I not done that, I may not have understood that English Comprehension is the key to acting.

- How did drama change your life at SLC?

It is true that my life changed enormously when I got in acting and ‘Midsummer Night’s Dream’ in particular. Until that point, I was just a boy who wasn’t a big achiever but I did that play and I could feel the temperature change. The School play was a big event and it would fill the hall. People absolutely loved it and I managed to steal the show. People talked to me who would have previously never done so. Young girls would say ‘hi’. This told me where my future would lie – everyone was saying ‘hi’ to this skinny little boy who looked as if he had come from India and who wanted money for the tuck shop. I would not have been an actor had it not been for St Lawrence College.

- What did you value most about your education?

I was the sort of kid who simply wouldn’t have passed any exams without learning the basics – reading, writing, arithmetic etc. However I ended up passing all my exams except Woodwork and that was only because the train was due to leave for London so, given the choice, I didn’t turn up for the exam. The fact that I passed every single other exam was testament to the excellence of the education. The general discipline instilled by Binfield really helped. He knew when to turn the pressure on. We were permitted to drift and explore our interests but when it came to that mock year it suddenly got very real. We weren’t allowed to drift any more. We could be in detention for hours if we weren’t up to speed. We had no more than 15 people in a class so there was nowhere to go unnoticed especially for a student like me who was prone to laziness and who tried to get by with charm. However the fact that I failed almost all my mocks but passed all my actual O levels is testament to the school. I still thinks that’s amazing for a kid who wasn’t academically smart like Dunnachie or Padiachy – I suspect that 2/3rds of the School were more like me too – but the teachers got us into university.

I have to say though that the girls were a big distraction! They started in the 6th Form from St Stephens but we were a bit young for them then. However by the time I had got to the Sixth form, they had their own boarding house over the road and were staying over. My first girlfriend in the Lower 6th was Alice Blaxland who is still a local and Francesca Gentilli, an Italian, was my next girlfriend in the Upper 6th. The Library was off limits after 8 o’clock as it was used by the senior boyfriends and girlfriends. It was an area where you could fool around but all very old fashioned though. The girl’s House was like Colditz and you tried to enter it at your peril. The 6th Form Club was a den of iniquity too.

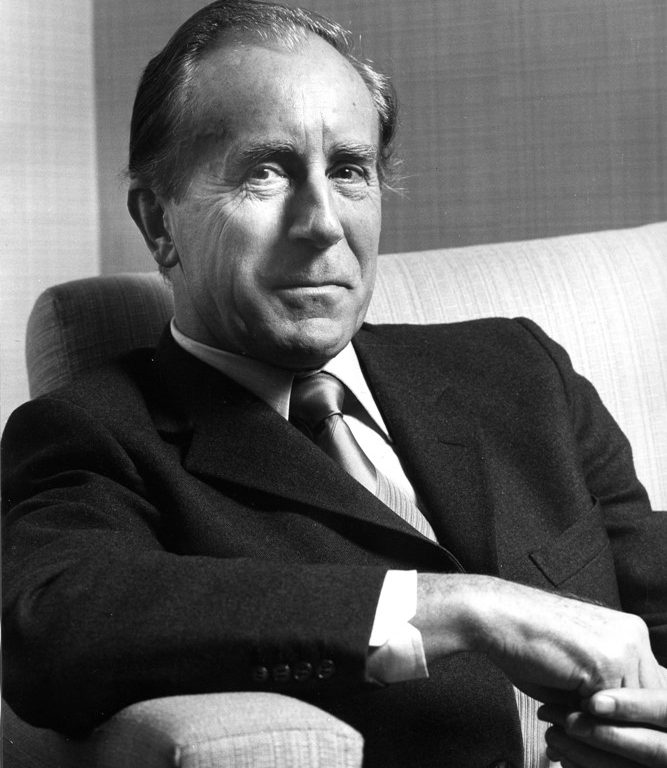

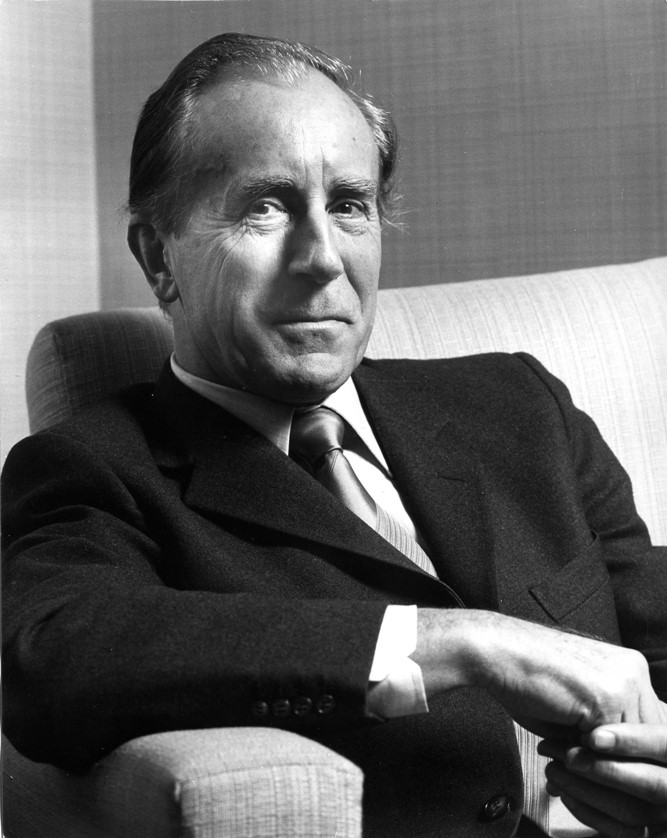

Sir William ‘Kirby’ Laing

Sir Kirby Laing, who died in 2009 aged 92, was unlikely to be anything other than a builder, a role he performed with skill and dedication throughout his working life. The family firm, John Laing & Son, which had been founded by his grandfather, was already nearly 70 years old when Kirby was born.

His father, grandfather and great-grandfather were all builders, not only of bricks, mortar and cement, but also of the family business. By the time Kirby and his younger brother Maurice took over the running of the firm after the Second World War from their father, Sir John, Laing had become a household name. Among the major postwar projects it executed were the M1 and Coventry cathedral.

In those days there was nothing unusual about the scions of a successful family taking over the direction of the business. In the case of the Laings, their “right” to the business was buttressed by a complex series of financial trusts.

But as well as being very successful businessmen, the family had a strong Christian faith. Kirby’s beliefs informed both his career and his extensive philanthropic work, much of it practised through his own charity, the Kirby Laing Foundation.

William Kirby Laing was born in Carlisle into a committed Christian Brethren family. He and his brother attended a small Christian public school, St Lawrence College, in Ramsgate, Kent. In later life, Kirby returned as Chairman and then as President of the College Council. The family maintained a long-term commitment to the school and a House (‘Kirby’) was named after him. The girls’ day house also carries the Laing name. Kirby went on to study engineering at Emmanuel College, Cambridge, which also has its roots in the Christian tradition. Maurice went straight from school into an apprenticeship at the family firm.

Kirby joined the firm in 1937 and was already a director in 1939 when, as a member of the Territorial Army on the eve of war, he was called up. He was subsequently released to work on military airfields, barrage balloon stations and other installations. In the same year he married his first wife, Joan Bratt, with whom he went on to have three sons. In 1943, he joined the army and served with the Royal Engineers until 1945. On demobilisation, he and Maurice were effectively handed day-to-day responsibility for managing John Laing & Son, with their father retaining the chairmanship of the board.

Kirby moved up to chairman in 1957, remaining in that post for the next 20 years, after which he made way for Maurice. During those two decades, he accepted numerous industry appointments and became well known for his views, somewhat unfashionable in the construction industry, that employees were the lifeblood of a company and needed to be treated decently. Throughout, John Laing & Son continued to grow and prosper with projects such as the Bullring shopping centre in Birmingham and the Windscale and Berkeley nuclear power stations.

John Laing & Son also began creating its own property developments. In 1978, fearing nationalisation of large construction firms if the Labour government was re-elected with a working majority, the property and construction businesses were separated, with Kirby taking on the chairmanship of Laing Properties.

However, the need to fund the development company with outside capital diluted the percentage of the shares held by the family, and in 1990 it fell victim to a joint takeover by P&O and Chelsfield. The takeover was opposed by Kirby, but the trusts accepted what appeared to be generous buyout terms. Proceeds were reinvested in a new property vehicle, Eskmuir Properties, in which the trusts still have important investments. In 2002, John Laing plc, then under the chairmanship of one of Kirby’s sons, Martin, sold its house-building business for £297m to Wimpey, and in 2006 the company itself accepted a takeover offer from Henderson Administration. Thus, the last link with the original business was severed.

Although Maurice, who died in 2008, was the better known of the two, serving as the CBI’s first president, Kirby left his mark by way of his extraordinary philanthropy through his £50m foundation, which he started in 1972. Enormous wealth was generated by the family firm, and successions of Laings felt the moral imperative to use their money for good works. The focus of the foundation, as with other Laing family trusts, is on the young, particularly the disadvantaged, in the fields of education and personal development, and on religious life.

The foundation has supported Emmanuel College, Cambridge, and also endowed academic posts, including the Lady Margaret’s professorship of divinity, the oldest established teaching post at Cambridge University, and donated to a number of medical charities. In 2006, the Whitefield Institute was reconstituted as the Kirby Laing Institute for Christian Ethics in recognition of the support given by the foundation. Other causes to benefit from Kirby’s munificence include housing organisations, ancient churches, music organisations and the Royal Albert Hall, for whom he served as president from 1979 to 1992.

A quietly spoken and driven man, Kirby was knighted in 1968 for services to the construction industry. His interests were fly fishing, travelling and listening to music. Like his yacht-racing brother, Kirby had an interest in sailing and was a member of the Royal Fowey Yacht Club.

His first wife died in 1981 and at the age of 70, he married for a second time, to Isobel Lewis. He is survived by her and the three sons of his first marriage.

William Kirby Laing, industrialist, born 21 July 1916; died 12 April 2009

Sir Maurice Laing CBE DL FRICS (Construction industry entrepreneur, first president of the CBI)

Sir Maurice Laing, who died aged 90 in 2008, was an unusual scion of the Laing dynasty of British builders and construction engineers which his father, Sir John, turned into an international institution. Sir John presided over the firm until his death in 1978, while his two sons, Maurice and Kirby, were groomed for the succession. Between the three of them they established the family name as synonymous with the construction of everything from houses to motorways, wartime RAF bases to cathedrals and mosques, bridges, tunnels and nuclear power stations.

From Christian Brethren beginnings, Maurice became the first president of the Confederation of British Industry, which, in 1965, brought together the power elite of British industry. It was a merger of Britain’s three most powerful employing groups: the Federation of British Industries, the British Employers’ Confederation and the National Association of British Manufacturers. Maurice was already president of the BEC when he was chosen to head up the new CBI, and his knighthood, in June 1965, came with that appointment.

What was remarkable about his speeches in that first full year of Harold Wilson’s government was not so much his searching views on what a Labour regime might have in store for industry, but his unorthodox tone toward the shop floor. He reflected an uncharacteristic liberal instinct, urging all employers to recognise the crucial importance of their workforce: “Employees are human beings and not just resources,” and must be treated “at all times with equity and fairness.”

The postwar record of industrial management had been a combination of arrogance and incompetence in the face of social change – for which many employers simply blamed the unions. Maurice’s views were different.

He was born in Carlisle and was eight when his father moved the firm’s headquarters, and the family, to London. He disliked formal education and his ambition was to fly aeroplanes.

Maurice was different from the rest of the family – notably from his older brother Kirby who, as a Cambridge engineering graduate, fitted far more easily and effectively into the world of building and big construction projects. Maurice was a sickly child with a speech impediment. The two brothers were sent to a private school, St Lawrence College, Ramsgate, its seaside location ostensibly to help Maurice’s health but primarily because it was a Christian foundation. However, he never settled and, in 1935, at 17, started work in the family firm as an apprentice builder at £1 a week. By then his health had improved and he became absorbed in the ethos of building site life. Almost all his workmates were from different backgrounds and it was also the middle of the economic slump. In his memoirs he confessed: “I am grateful that I started work in 1935 because if I had gone to university I would have started at a later age and would never have seen the depression. It has influenced my whole life”.

His first managerial role came in 1938 when, immediately after the Munich agreement, the Chamberlain government began building new airfields. Laing and Wimpey were given major contracts initially to build barrage-balloon stations; Wimpey building stations north of Derby and Laing south of that point. Maurice was put in charge of seven balloon sites, plus one main RAF station, and, at the age of 21, had 5,000 men working for him. He was now working an 80-hour week on the building sites and driving fast cars, his second obsession after aeroplanes.

In March 1940, shortly before Dunkirk, he married Hilda Richards from a religious Ramsgate family and then enlisted with the RAF – though his work exempted him from military service. His father sought to stop him. Another complicating factor was that his wife had became seriously ill with tuberculosis. For the next two-and-half years he remained torn between his desperate wish to be in the RAF, his wife’s illness and his father’s insistence that he remained in charge of building airfields (Laing built 54 RAF stations during the war.) Sir John persuaded the head of works department at the Air Ministry to stop his son’s call up. A furious Maurice threatened to quit and risk imprisonment unless he could join.

Finally he managed to join the RAF at the end of 1942, won his pilot’s wings after a year but was summoned back to England because of his wife’s worsening health. It was not until late in 1944 that he finally fulfilled his longstanding ambition to fly in RAF wartime operations. As a flying officer he piloted the second British glider carrying troops across the Rhine and was lucky to survive.

In 1945, Sir John handed day-to-day management to his two sons. Kirby, the more qualified executive, was the first to take on the role of chairman with Maurice as his deputy, though not formally until 1966; he succeeded Kirby as chairman 10 years later, a post he held until retirement in 1982. In 1988 he was appointed life president of the company.

While Kirby was responsible for Laing’s international expansion, Maurice was in charge of many domestic contracts. At this time, Laing’s were pioneering Britain’s motorways, building 53 miles of the M1, rebuilding Coventry’s new cathedral (on a no-profit contract), nuclear power stations and the London Central Mosque at Regent’s Park. It was probably the company’s most successful period. Maurice was 58 when he became company chairman in 1976 and chose to restructure the company into a property section and a separate construction group. It was a period of widespread industrial reorganisation and Maurice who was made a director of the Bank of England in 1963 (he served for 17 years) believed he was following the financial fashion in decentralising the group. But by the time he retired in 1982, the property company had been sold after a hostile bid and the global construction scene was changing character.

Fortunately for the family fortunes, in 1972, Sir John had shrewdly set up a complex system of trusts as well as charitable foundations for his sons and grandchildren. Even so the company had to further restructure in 2001 disposing of much of the original business and restyling itself as one of Britain’s principal investors, developers and managers of building infrastructure. Its current role is to help bring together major projects in the public and private sector such as railways, roads, hospitals and schools.

Outside the family business, Maurice’s main preoccupations were sailing, a deep attachment to complementary medicine and the Church of England. He is survived by his wife and their son John.

John Maurice Laing, industrialist and benefactor, born February 1 1918; died February 22 2008